Modern Vancouver is more than part of the eco-revolution; it may be the hub of an existing eco-evolution. It’s no wonder locals have affectionately known this green city for decades as the “city in the rainforest”.

Unlike most comparable metropolitan areas, Vancouver’s unique and notable natural beauties-water, mountains and lushness-are indivisible. This endemic desire to keep the fastest growing city in Canada lush is exemplified in the acceptance of new, green technologies in each of Vancouver’s distinct areas.

Few innovations leave such physical evidence of Vancouver’s growing green evolution than architecture. Since June 2008, Vancouver requires new developments to meet LEED silver specifications. By the year 2010, more stringent LEED gold building codes will be in place. Vancouver has committed to becoming a carbon-free city by 2030.

As a pilot initiative to promote sustainable building practices, the city chose the National Works Yard, a 12-acre engineering operations center designed by the Canadian firm Omicron. The two administrative buildings are LEED Gold certified for the choice of site, use of local and recycled materials, water and electrical efficiency and indoor environmental quality. The Yard was also designed to accommodate the growth of operations for the next 10 to 20 years.

The booming North Shore showcased sustainable building for the future when the newest public school exceeded the already ambitious green mandates for energy conservation, construction practices and waste recycling.

The philosophy that sustainable can be beautiful resulted in the stunning contours of the 15-story BC Cancer Research Centre, a state-of-the-art facility home to eight specialty laboratories. The Centre was designed in partnership with IBI Group and Henriquez Partners and was awarded LEED Canada Gold.

An integral part of a vibrant, sustainable urban core is affordable housing. Another Henriquez Partners project is the Lore Krill Co-op housing project.

The Co-op’s two eight-story buildings sit on a landscaped podium and remain within the 75-foot height limit. The front of the building has a continuous canopy that provides rain protection, and the ground floor is set back to accommodate a future streetcar stop. The rear elevation is set back, and its windows are angled for views down the lane. The five landscaped roof terraces have gardens for growing vegetables and decks with views of the city and the mountains. There is a large courtyard providing a common area for the residents with a waterfall that masks neighborhood noise. Bridges across the courtyard link the two buildings.

The Co-op is named in honor of Lore Krill, a co-op and poverty activist who worked tirelessly for the residents of the Downtown Eastside and died in 1999.

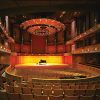

The Scotiabank Dance Centre is one of many examples of architecture as a catalyst for raising the profile of the arts in Vancouver. The Centre was designed by Architectura in collaboration with the renowned Canadian architect Arthur Erickson. The seven-story, glass-enclosed building is a purpose-built, shared use facility that provides a diverse dance community with a new home.

The rise of green building in Vancouver has prominent international connections such as the involvement of British architect, Norman Foster. Foster embodies, in many ways, Vancouver’s dare to dream with such looming successes as the 61-story Shangri La, the city’s tallest building.

Other notable additions to the Vancouver skyline are set to include two luxury condo towers. The Residences at Georgia are luxury condos sitting atop the historic Hotel Georgia in the heart of downtown. The Residences at the Ritz Carlton are also currently under construction and set to offer all the amenities afforded to guests for residents.

Vancouver has also begun plans for hosting the 2010 Winter Olympic games. It is leaning toward plans to ban traditional gas and diesel-powered vehicles used in the games. Almost $20 million will be used to develop model hydrogen transportation for the games.

But the city hailed as the World’s Greatest City in 2005 has marathon plans for a globally green message: the traditional Olympic torch relay may be extinguished, in noting the concern over global warming and highlighting Vancouver’s sustainability. Any Olympic torch used in Vancouver may be solar powered.

Southeast False Creek was once the foot stand for the city’s shipping and marine storage facilities. These days, False Creek is now on deck for an updated green design, and also soon to play host to the 2010 Olympians. Sleek condos will be chic hosts to bobsledders and speed skaters, and Vancouverites have literally camped out for days, in a promotional contract lottery to be the first to move in after the Olympic Village closes. The False Creek community may be a nine-block square, but it is still fit for LEED gold standards. Half of the buildings will use lawns and greenery on their roofs, to enhance water capture and natural insulation. The other half will have rainfall water reclamation systems. The water system will reduce potable consumption by 50 percent over traditional systems. And yes, there is weekly community-wide compost pickup. The development also intends to limit or even eliminate residential gas motor access.

Vancouver is no stranger to pageantry, however, and may be excused some of the confidence instilled by the highly successful World’s Exposition in 1986.

The Exposition of that era led to a massive architectural redesign of the Vancouver Harbour area. The Vancouver Exposition and Convention Centre is undergoing an enormous expansion. With a budget of over $800 million Canadian, the city has enlisted a multi-national advisory board to ensure the focus of sustainability efforts will be on best practices and their relationship to standards and certification rather than merely adopting a code or standard that may not stand scrutiny by the time the facility is open for the 2010 Olympic Games.

In order to ensure that the expansion and existing facility are fully integrated, a glass-walled connector will link the facilities, providing attendees with picturesque harbor views. Featuring floor-to-ceiling glass throughout the expansion, the project will also include a six-acre living roof, one of the largest of its kind in the world. This unique ecosystem is one of many environmental innovations included in the expansion.

It’s almost impossible, not to suspect an early historical decision parlayed Vancouver’s natural beauty into their current green building renaissance: Stanley Park is at the heart of Vancouver. As Central Park softens New York, the sprawling one thousand acre lodestone called Stanley Park leavens Vancouver’s rise. Dedicated in 1889, Stanley now has more than 8 million visitors a year-and more than 500,000 trees.

In every real sense, Vancouver has already had the world, and the future, come to appreciate the greening dream of their ambitious energy.