America’s neighbors to the north know a thing or two about trekking forward into 21st century territory. Canada’s largest metropolis and capital city, Toronto, is quickly becoming an architectural hot-spot, eager to meet the demands of a global economy competing to create an excellent quality of life for its residents and visitors. World-renowned architects are flocking to the city to create unique and environmentally conscious designs, permeating the city with escalating tourism and nudging its way into the global marketplace.

America’s neighbors to the north know a thing or two about trekking forward into 21st century territory. Canada’s largest metropolis and capital city, Toronto, is quickly becoming an architectural hot-spot, eager to meet the demands of a global economy competing to create an excellent quality of life for its residents and visitors. World-renowned architects are flocking to the city to create unique and environmentally conscious designs, permeating the city with escalating tourism and nudging its way into the global marketplace.

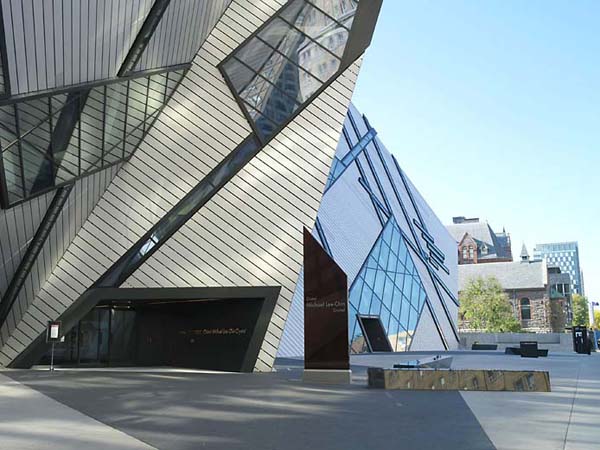

“Architecture is a language,” according to Daniel Libeskind, and his artistic visions speak volumes. His most recently completed project has transformed Toronto’s urban landscape and Canada’s largest museum. The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) recently underwent a facelift now titled, Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, appropriately named after a ROM benefactor who donated $30 million to the museum.

Aerial photographs show the museum’s expansion in the foreground of Toronto’s skyline, as if the city is holding a fistful of jewels in the palm of its hand. An amazing pile of glass, the wing features fragmented lines and zigzag patterns, yet appears amazingly streamlined. This $270 million (CAD) project bridges the gap between the nearly 100-year-old museum and 21st Century art.

Across the street, the architectural firm of Kuwabara, Payne, McKenna and Blumberg (KPMB) created a boxy, ultra modern renovation to the Gardiner Museum of Ceramic Art. A limestone exterior coupled with floor-to-ceiling windows creates a unique vision hinting at the style of art found within its walls. It was designed with the option of continued upward expansion if so desired in the future.

Simultaneously historic and forward-moving, Radio City/National Ballet School was home to the first Canadian television transmission studios. The definition and epitome of mixed-use architecture is found here now, integrating the townhouse-style architecture alongside leaping stories of glass and steel. Created by the aforementioned KPMB Architects working in conjunction with Goldsmith Borgal and Company Ltd. Architects, the historical feel of the district remains intact while being flanked by high-rise condos in the same breath.

Buildings that put the “fun” in function

The Ontario College of Art and Design provides its students with a muse right on campus. The Sharp Centre for Design, created by Will Alsop, is a whimsical yet functional addition to the relatively dreary buildings of the school in comparison. Appearing to be a black and white checkered pencil box held aloft by large colorful crayons, the building is also practical, housing office space, theaters and art studios for students and staff alike.

Whimsy continues in the architecture of the Bata Shoe Museum. As if a museum dedicated solely (pun intended) to shoes is not selective enough, the plethora of footwear is all neatly housed in a shoebox-like structure designed by Raymond Moriyama. The shoe theme is carried throughout the building, with all signage for exhibits made of leather; a homage, of course, to the museum’s historical collections.

Environmentally Friendly Hotspots

What better place to conduct groundbreaking genetics research than in a futuristic building oozing scientific and technological advancement. The Terrence Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, University of Toronto’s newest addition, towers over neighboring buildings It is a feast for the eyes when lit up at night, the windows aglow with various hues of red, yellow, green and blue. Appearing somewhat top-heavy yet structurally sound, the building houses laboratories, offices, lounges and cafes while utilizing energy-saving systems. The Toronto-based architectural firm Alliance, along with European- and US-based Behnisch Architekten created this $100 million (CAD) structure, locking Toronto’s reputation for biomedical advancement and research into place.

In this day and age, expanding living space in congested cities usually embodies green initiatives, designed to protect the environment. Leonard Avenue Pre-Fab Rooftop Apartments, designed by Levitt Goodman Architects, Ltd., is one example of this practice. Building upwards rather than outwards, the tenants of 26 new housing units placed on the roof of an existing apartment complex enjoy a green roof common courtyard outside their front doors. Construction was completed in a scant two weeks, with most of the labor being carried out at an off-site factory, making the project minimally invasive to both the building’s existing tenants and the surrounding neighborhood.

Toronto’s suburb of Scarborough houses the Thomas L. Wells Public School, designed by Baird Sampson Neuert Architects. The school is proud to boast its low impact on the environment while sustaining a high educational impact on students for the 21st century. Solar energy, a rooftop garden and energy efficient appliances will keep the school running smoothly and inexpensively, all the while teaching tomorrow’s generation about the importance of caring for the environment.

Diamond and Schmitt Architects are revitalizing a previously unused portion of Toronto’s Central Waterfront in conjunction with the Toronto Economic Development Corporation. An energy-efficient Corus Entertainment building will soon grace its banks, creating a mixed-use community that is environmentally sound while raising the job base and economic growth potential for this previously under-utilized area of the city.

With all of this development taking place in the heart of Canada’s bustling capital city, one factor remains consistent: bridging the gap between history and the future while utilizing environmentally conscious methods and materials ensures Toronto’s success as a city of tomorrow while respecting the foundation on which the city was built in years past. Clean and modern designs set against historical buildings propel the city forward as a model of form meeting function and combines a respect for the future along with a remembrance of the past.

[latest articles]

Selva Restaurant: A Design Inspired Dining Experience in Amsterdam

New Home of Toronto’s Museum of Contemporary Art

Nordic Architecture and Sleek Interior Design

Charting a New Course at Compass House