A capital city is often defined by a solitary architectural icon that seems to offer the quintessence of a nation and its culture. Brazen, innovative, aloof: the symbol of the Parisian character is inherent in the stiff arches and towering pinnacle of the Eiffel Tower, one of the most recognizable landmarks in the world.

“We need to stop thinking of Paris as a museum city,” said Jean Nouvel, the architect whose design recently won a fiercely contested bid to build the 988-foot-tall Tour Signal in La Défense. The building has been proclaimed the most important work of architecture in Paris since the Eiffel Tower.

For decades, Paris has been delimited by a veto protecting the city’s skyline, setting a limit to skyscraper heights at 121 feet since the mid-1970s. The main reason for this seems to lie with the poor reception received by the monolithic Tour Maine-Montparnasse, France’s tallest skyscraper at 689 feet.

The Tour Maine-Montparnasse was completed in 1972 and exudes the leitmotif of that era-size over subtlety. A rather characterless steel and glass colossus, it contrasts starkly with its surroundings; the immediate vicinity is classic Hausmann territory. Georges-Eugéne Haussmann was the urban planner hired by Napoleon III to modernise the city. He produced a Paris of uniform building heights and broad tree-lined boulevards, ideal for repelling pesky Parisians prone to revolt. Put another way, it is the classic romanticized vision that Hollywood has of Paris, a vision which some believe has trapped the city into becoming a metropolitan-sized time capsule, constraining developers.

Change is afoot. Jean Nouvel outgunned some of architecture’s leading luminaries, including Norman Foster and Daniel Libeskind, to secure the Signal Tower bid. The Frenchman’s building was praised for its eco-friendly materials and mixed usage, bringing together apartments, hotels, offices and retail premises all under one roof for the first time in France. The structure itself consists of four blocks piled one on top of another, with atriums forming huge windows, each facing in alternate directions.

Such utilitarian use of space is always welcome in a city with a massive housing shortage. While, as a design, it may lack the visual fireworks of a Libeskind or Foster, it offers up its own ingenuity for a world striving for sustainable development.

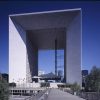

The area earmarked for the Signal Tower is La Défense, a commercial development located in the western inner suburbs. This new quarter is strikingly modern, almost inhuman, and has often been criticized for lacking warmth. Here one will find the headquarters of major corporations like energy giant Total. One could view it is as Das Kapital writ large in steel and glass, and feels like a ghost town after rush hour.

That said, there is beauty to be found among the formalist office blocks. The Grand Arche de La Défense is a bold architectural statement-a massive hollow cube offering a square eye through which to view the business center. Acting as both a visual entrance and exit for La Défense, it also serves as unique office space.

And now a new breed of high-rise towers is coming to humanize this zone.

A day after Nouvel was confirmed the winner, another bidder, the investor Hermitage with Jacques Ferrier Architectures, announced they would construct their H Towers in a municipality bordering La Défense. La Défense itself will see the addition of another tower by another architect gaining popularity, Christian De Portzamparc. This urbanist has a very distinctive prismatic style, coalescing oblique shapes into a cohesive whole, as his design for the Tour Granite exemplifies. And then there is the Phare Tower, a striking design, recalling Frank Gehry in its fluid, almost alien form.

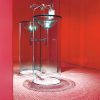

Paris has also been making waves in the hotel world. Just a third of a mile from the Champs-Elysses is the Hotel Sezz, a frequent recommendation in top 10 lists of the world’s hippest hotels. It’s not hard to see why. The hotel’s furniture is custom-designed by Christophe Pillet, a prodigy of Phillipe Starke. Colors and lines are touted as severe and masculine, but the balance of a vibrant palette and taut modern lines is immaculate. Rooms are ultra modern and yet still warm and welcoming.

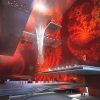

Another refreshing lodging option for those staying in the city is Kube. It lies tucked away down the quiet passage Ruelle in Montmartre, a quarter made famous by Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s film, Amelie. It vaunts itself as a classic slab of retro-future, which seems an oxymoron gone too far until you see the interior, recalling the set of films like 2001: A Space Odyssey. A line of Eero Aarnio’s 1968 classic bubble chairs hang on slender chains in the bar, while jellyfish tendrils trail pink light down from the ceiling. It’s clever stuff, re-imagining the previously imagined, and provides a novel feast for the eyes.

Museum-wise, Paris has always been cutting-edge. Take the Pompidou Centre. It feels familiar now, passé even, a result of having been echoed in the modern interior design of modish restaurants and bars, where the nuts, bolts and piping are laid bare. Yet this idea of a high-tech exo-skeleton represents a watershed moment in architecture, and as such is a must-see.

The Louvre, on the other hand, is a more staid and stately affair, befitting a former seat of power. The palais is awash in Rococo refinement, wearing its history on every cornice and column. Little wonder that Francois Mitterand’s legacy, the four glass and metal Louvre Pyramids, caused such a sharp intake of breath in 1984. From a distance of two plus decades, I.M. Pei’s designs for a new entrance to cope with swelling visitors have aged well, offering a tantalizing relief from which to view the grand old dame behind.

Paris finally seems to be escaping the quixotic vision the rest of the world has of it, transfiguring its skyline with challenging high-rise structures and embracing the exciting possibilities of reaching up to touch the sky.

[latest articles]

Selva Restaurant: A Design Inspired Dining Experience in Amsterdam

New Home of Toronto’s Museum of Contemporary Art

Nordic Architecture and Sleek Interior Design

Charting a New Course at Compass House