A Scottsdale-based architectural design competition is approaching real estate flipping from a radically different perspective.

“Strip malls litter our landscapes,” said Claire Schneider, senior curator at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (SMoCA), the competition sponsor. When an owner sets out to maximize use at an underperforming strip center the existing building is usually trashed. The average strip mall design is equivalent to architectural debris.

SMoCA was determined to change the trend. Prompted by a conversation at a cocktail party, SMoCA director Susan Crane broadcasted an international architectural challenge to creatively re-use and configure – as opposed to re-build – an average suburban strip center. SMoCA’s Flip a Strip competition posed an essential post-suburban question: can an unattractive, awkwardly designed strip mall be imaginatively re-used?

“Only five museums in the country have architecture departments,” said Schneider. She cites a growing interest in architecture among emerging professionals with untapped creativity and energy. Schneider was attracted to SMoCA because of its interest in new challenges.

“We wanted to address a really important issue,” Schneider said. “Strip malls are things we don’t love, but are an important part of our infrastructure.” The competition focused on three existing Phoenix-area strip malls. Entrants selected one property and developed an economically viable and culturally meaningful reinterpretation of its design. Existing improvements could not be removed.

Flip a Strip was designed to promote a dialog on re-use and did not involve a design-build phase. However, the primary criterion was for financial feasibility within the re-use context. Different jurors evaluated architectural quality, a secondary factor.

Crane consulted with Casey Jones, a principal at Jones/Kroloff and former member of the General Service Administration’s Design Excellence Program. The ten finalists were unveiled SMoCA’s Flip a Strip exhibition that opened Oct. 4, and three were granted awards of excellence.

The Flip a Strip challenge touched a nerve internationally and roughly 175 entries were received from 11 different countries – the majority unsolicited.

Schneider views the enthusiastic response as confirmation that SMoCA initiated an important conversation. “This is a first tier city project,” she said. Schneider believes SMoCA’s relatively small size enabled them to foster the out-of-the box competition. “A small institution has some nimbleness,” she said. “We can dream big.”

Schneider’s hope is that Flip a Strip will also prompt property owners to think beyond existing limitations. Strip malls were originally intended to serve small neighborhoods via a traditional strip mall mix of grocery, pharmacy, video rental, dry cleaner and local restaurant. With the advent of big box destination grocery stores that design typology is now obsolete.

Yet there is still a vast supply of generic, boxy strip centers. Despite their lack of visual appeal, strip malls serve a community-centered purpose. “During years spent living in Los Angeles and southeast Seattle, most of my favorite restaurants and shops have been in strip malls,” said Mike Jobes, principal at Miller Hull Partnership in Seattle. He is intrigued with the low-cost nature of strip mall use. “That is why the most authentic ethnic restaurants and shops are found in strip malls,” he said. “They are the only spaces affordable to immigrant entrepreneurs opening their first shops.”

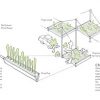

Miller Hull’s Bumper Crop contest submission proposes an aeroponic parasol for the strip center parking lot. Cash crop farming is stacked above the surface parking. Reclaimed city water, filtered through a membrane bioreactor, supports the elevated garden. Jobes envisioned a strip mall turned oasis, hoping the organic farming aspect would bring organic farmers, tenants and shoppers together in one community.

Bio-farming was a common competition theme. “Many young architects are thinking about urban farming,” Schneider said. “Flip a Strip is a brilliant way to showcase this.”

The finalists included Chia Mesa, submitted by Roger Sherman Architecture & Urban Design in joint partnership with UCLA’s cityLAB. “We envisioned a local green market for the neighborhood,” Sherman said. Multi-level hydroponics technology sprouts from Chia Mesa’s re-designed elevations. The costs to convert would eventually be recouped through the sale of hydroponically grown produce and income from an existing steakhouse, converted to a bio-diesel fuel station.

Other entries were more fiscally organic. “We accepted the condition of the strip mall,” said Marlene Imirzian, principal at Marlene Imirzian & Associates. Her concept focused on the strip center’s low-budget origins. “We took the competition brief real seriously,” she said of the financial feasibility requirements. Imirzian’s diVert concept projects a total budget of $475,000, significantly lower than many entries.

Imirzian envisioned a re-branding program that could be executed and maintained by the average owner. Individual strip centers would develop a distinct architectural brand and operate similar to a franchise. The diVert concept includes sunscreens with integrated signage on the strip center’s façades. Imirzian described the sunscreens as “a monolithic super-graphic.” When closed, they double as full-sized signage.

DiVert also proposes a re-facing of the building skin with a photo-catalytic, air-cleaning coating manufactured in Italy. The coating, a functional amenity, also lends cachet to the brand. Bollard-style outdoor seating and lighting elements would enable nighttime rental of the space after hours. “We are adding revenue for property owners and adding community space for houses adjacent to the center,” Imirzian said.

Reorientation of the isolated strip center to community use is central to the Flip a Strip concept. The exhibition will maintain the interactive focus. “My role has been to explain [the entries] in a manner people can understand,” said Schneider, who views herself as interpreter between architect and end-user. To that end, she has avoided the traditional storyboard method of presenting static design proposals. Live sections of a Bumper Crop farm will be growing at the SMoCA Flip a Strip exhibit running through January 18. A section of algae from Chia Mesa will present the concept in a tangible way. “People can interact with these on a one-to-one scale,” Schneider said. “The exhibit is for anyone living in the city, not just those interested in architecture.”

[latest articles]

Selva Restaurant: A Design Inspired Dining Experience in Amsterdam

New Home of Toronto’s Museum of Contemporary Art

Nordic Architecture and Sleek Interior Design

Charting a New Course at Compass House

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

The post content and features are really looking with full of elegance. And the existing information of this post really makes me crazy about it. This one is really one of fully informative post. And the existing information of this post really increases my amount of knowledge about it.